The first wave of an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.9 hit Tokyo at 11:58am on 1 September 1923. By the time the fire ended seventy-two hours later, almost fifty percent of the city was burnt, totaling thirty and a half square miles and 370,000 houses. Nearly 100,000 people had died. The densely populated and poorer eastern parts of Tokyo suffered the most. Wooden buildings easily caught fire; narrow alleys allowed the fire to spread; and the lack of parks meant the fire could move in all directions. The city lived under martial law from 2 September until 15 November. In that time, tens of thousands of Koreans were detained and imprisoned under suspicion of sedition. These actions led some officials to demand civil training for disasters.

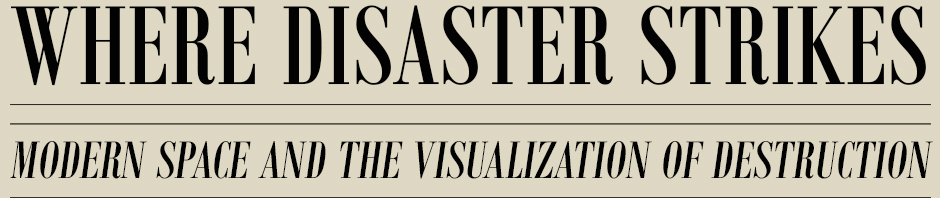

As this map of the fire shows, strong and varied winds sent fires throughout the city and, because the fire came while many were preparing lunch, dozens of individual fires began together. Through the small dots, arrows, colors, and diagrams, this map tries to communicate the complexity of the chaotic destruction.

Relief Information Bureau, (東京帝国大学羅災者情報局調查), “Map of the fire of Tokyo (帝都大震火災系統地図)” (1923)

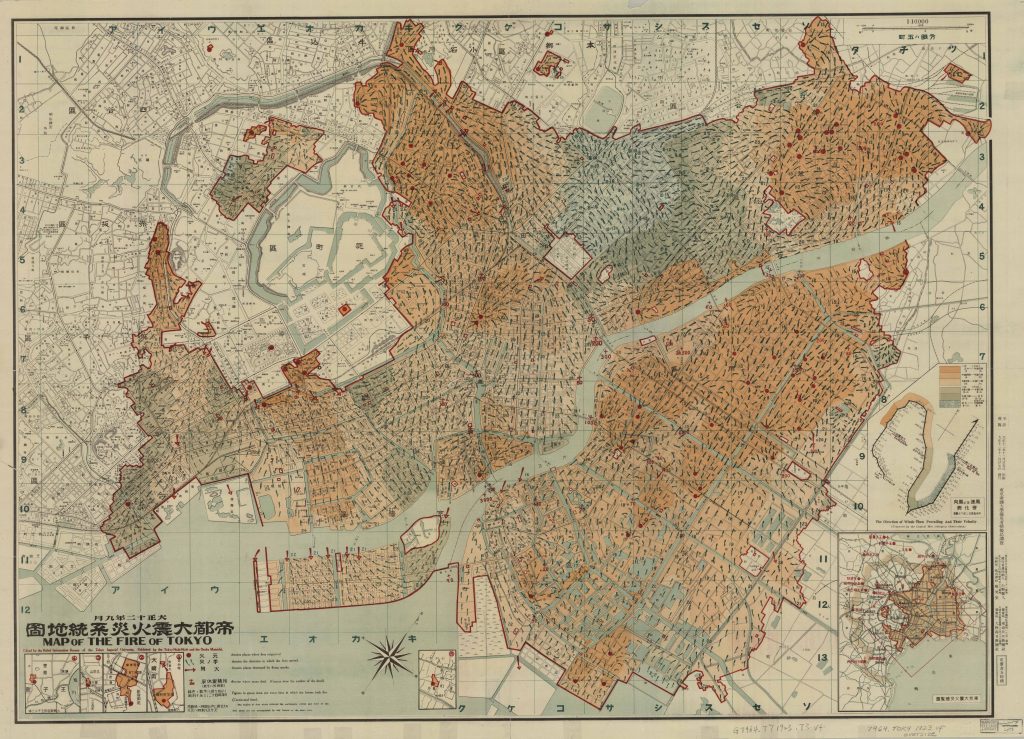

Endō Ichitsugu, “Town planning in Japan…” (1924)

Sankaku & Company, “Tokyo” (1929); Gift of American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Nov. 8, 1958

What was it like?

“Moka ni kakomarete fushigi ni yaki-nokoritaru Asakusa Kannon” (Asakusa Kannon, which miraculously survived the flames, even though surrounded by raging fire) (1923); Original from British Museum, 2011.3024.3

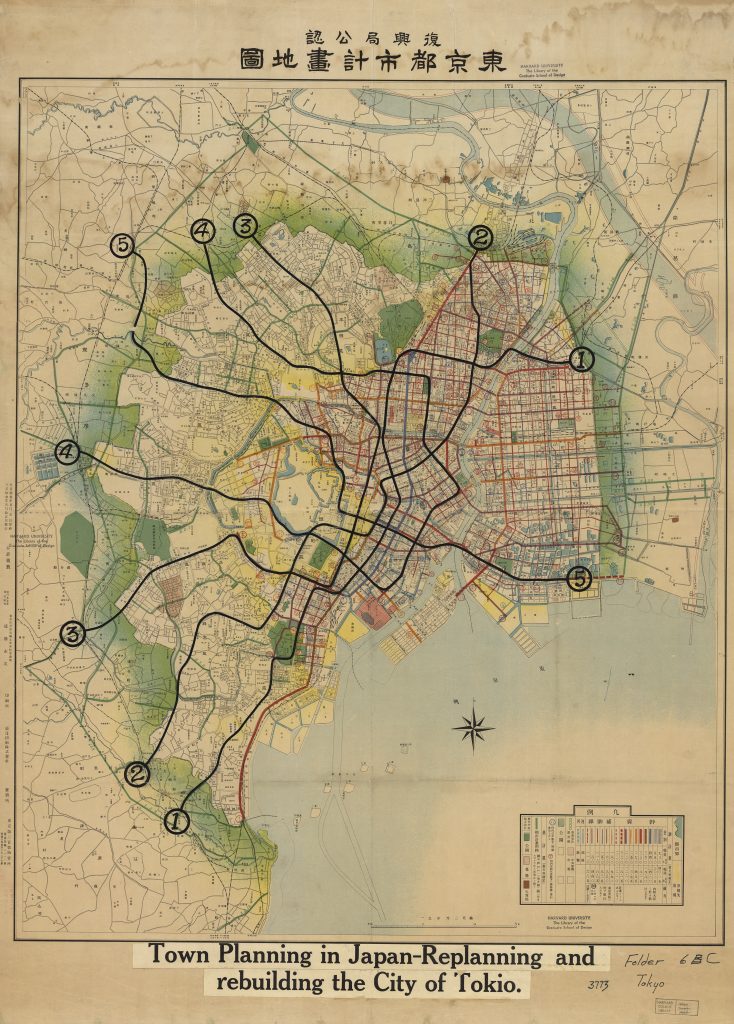

Images and narratives of the fire in Tokyo spread quickly throughout the world. Through postcards, pictures, short movies, newspaper reports, and lithographic prints, the world could both mourn the losses in Tokyo and also explore the spectacle of the devastation. Images of the ruins in Honjo, for instance, brought tourists from all over Japan to witness where 38,000 refugees had died after they were trapped in the lot of an old army clothing depot, which they had thought safe. Almost two million people visited Tokyo within two weeks to see the city for themselves.

One of the most striking depictions of the fire was the Pictorial Account of the Great Earthquake in the Imperial City (Teito daishinsai gaho) published on 30 September 1923, just short of a month after the disaster. In fourteen lithographs, this volume both documents the experience of the chaos and also constructs a shared mythology of the fire. Here, for instance, the artist depicts the bodhisattva Kannon saving the temple in Asakusa from destruction while letting the Nakamise shopping area burn nearby. By visualizing the disaster and drawing witness to these sites, these circulating images established shared narratives through which Japan and the world could understand the space of the city, past, present and future.

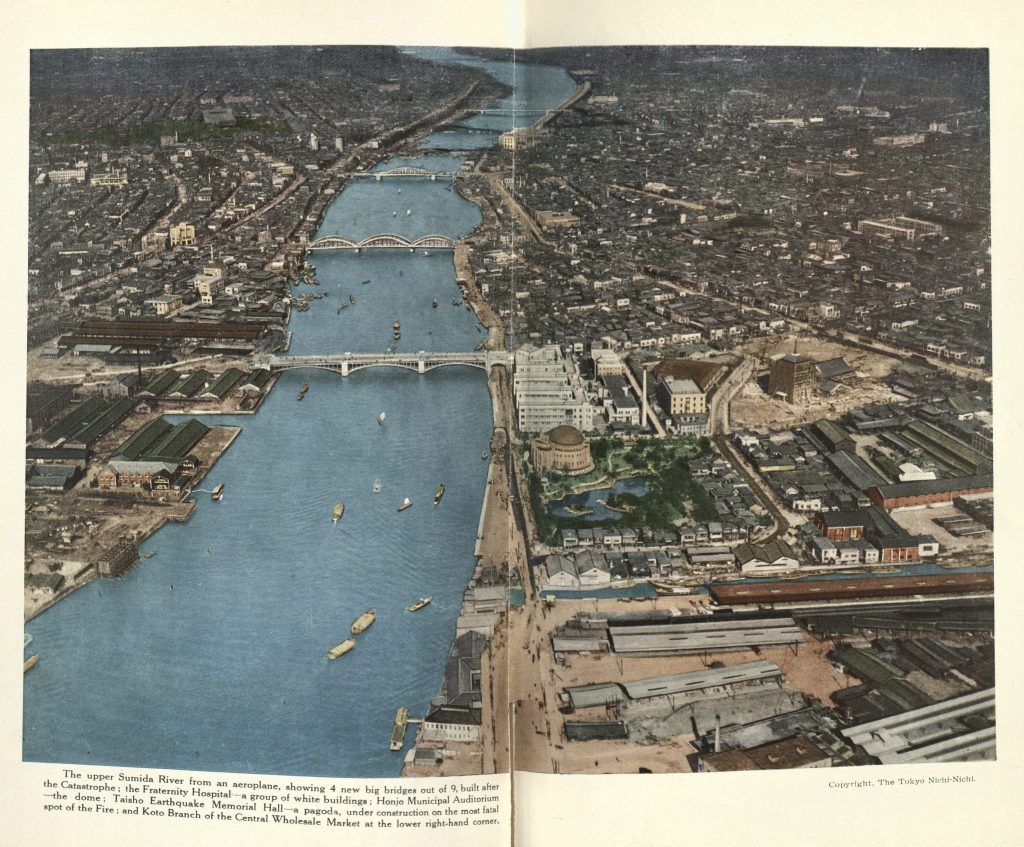

Rebuilding Tokyo

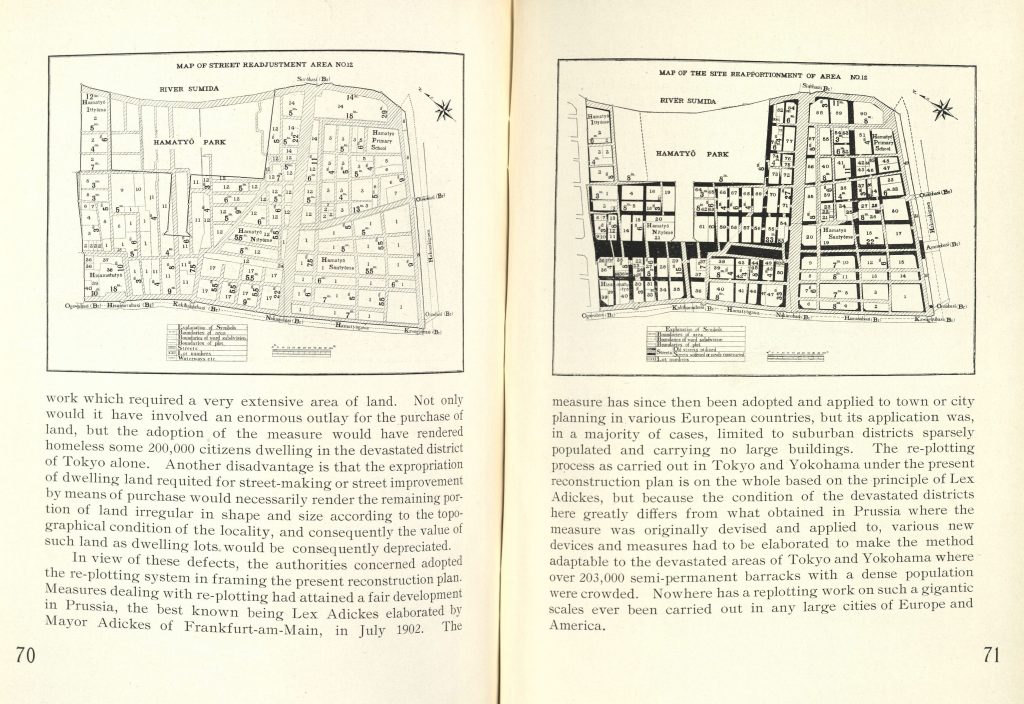

Confronted by the largest urban fire in modern history, Tokyo responded with the most ambitious rebuilding project to date. The government passed the City Planning Act in 1924 that allowed the city to claim up to ten percent of anyone’s land without compensation for the readjustment of city plots. As this rebuilding commenced and especially once it was completed, the city proudly advertised the successful recreation of itself not just to the Japanese people but to the world. This English-language volume by the Tokyo Municipal Office, for instance, emphasizes that the city has added 3,630,000 square meters of streets to make wider and safer travelways, that the city now has 3 large parks and 51 smaller parks, and that the city moved 203,000 houses to make readjustment possible. The volume concludes triumphantly:

“The reconstruction of Tokyo has not meant merely restoring [the city’s districts] to their former condition, but has meant creating them anew as modern cities. Especially remarkable in this respect has been the relaying of the streets, involving a complete revision of city lots. This land adjustment was on a scale without precedent in any city of the world, and marks an epoch in the history of city planning.”

Zenjirō Horikiri, ed. Tokyo, Capital of Japan; Reconstruction Work. (1930); E. G. Stillman Japanese Collection; Courtesy, Widener Library

Zenjirō Horikiri, ed. Tokyo, Capital of Japan; Reconstruction Work. (1930); E. G. Stillman Japanese Collection; Courtesy, Widener Library