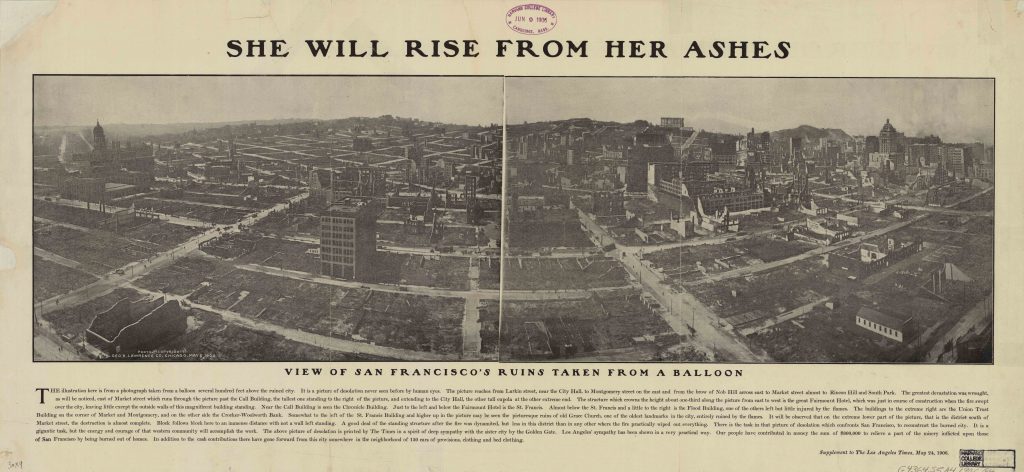

For three days beginning on 18 April 1906, San Francisco was on fire. By crippling the city’s water mains, the earthquake that began at 5:12am left the city vulnerable to massive fires. By 20 April, almost five square miles of destruction had claimed 28,188 buildings. Huge refugee camps were opened in city parks and neighboring Berkeley, some of which remained open for more than two years. Amidst this devastation, new cheap and portable cameras allowed professionals and amateurs to record the destruction as never before. George R. Lawrence, as you can see here, rigged a custom camera on an elaborate system of kites—the “Captive Airship”—to produce expansive panoramas.

As the city moved forward, plans for renovation exposed longstanding racial tensions. During the fire, Chinatown had been heavily damaged and left unprotected from looting by policemen who focused on other parts of the city. Indeed, newspapers and magazines lamented the destruction but argued that the fire gave the opportunity to relocate Chinatown, which these white reporters and businessmen felt occupied too central a portion of the city. Despite this pressure, the property owners in Chinatown successfully lobbied the city and defended their neighborhood.

Geo. R. Lawrence Co., “She Will Rise from Her Ashes …” (1906)

R.J. Waters & Company, “[San Francisco, California…]” (1906)

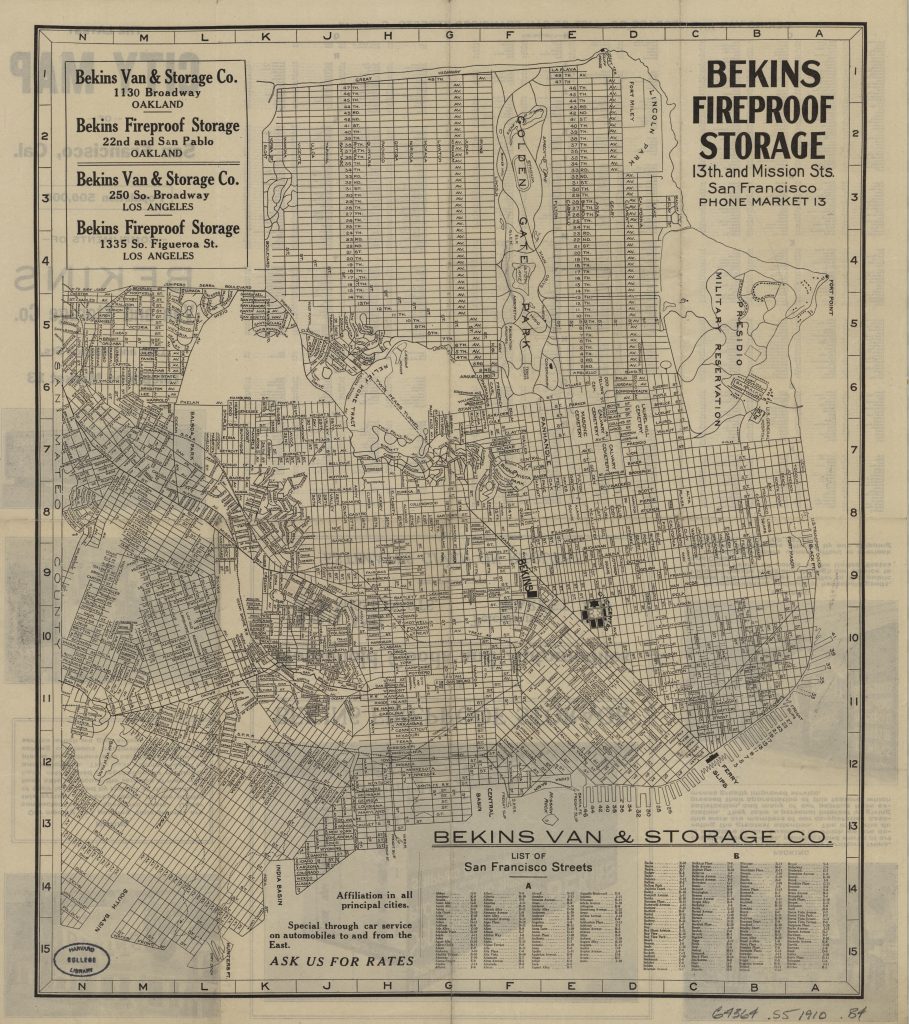

Bekins Van & Storage Co., The latest city map of San Francisco, Cal. (1910s)

What was it like?

“I have only a vague kaleidoscopic vision of whirring at whistling speed through a city of the damned. We tried to make the fallen Brunswick Hotel at Sixth and Folsom Streets. We could not make it. The scarlet steeplechaser beat us to it, and when we arrived the crushed structure was only the base of one great flame that rose to heaven with a single twist. By that time we knew that the earthquake had been but a prologue, and that the tragedy was to be written in fire. We went westward to get the western limit of the blaze”

James Hopper was a reporter for the San Francisco Call at the time of the earthquake and fire. After a late night at the opera, he woke to a shaking city. He dressed and hired a passing car to take him around the city throughout the day. In the June issue of Everybody’s Magazine, he published this account of the first day of the fire and earthquake. With phrases like “scarlet steeplechaser,” we can see Hopper’s place among the colorful—often lurid—newspaper stylists of the turn-of-the-century.