Mirror, mirror on the wall

ø

Who’s the fairest of them all?

I became fascinated with the character of Keba in Aminata Fall’s “The Beggar’s Strike.” Keba, a righteous man working for the city municipality, spent his childhood in poverty. He emphasizes the distinction between his mother, to whom he refers as one of the “genuinely poor,” and the beggars in the city “who do a real wrong to humanity.” If all a person has is dignity, then his world centers around it. When Keba sees a beggar asking for alms and when he sees others’ reactions ranging from annoyance to disgust, Keba has to reconcile with the inherent dignity of a beggar. His response then becomes that the people who ask for alms are not real beggars. If no one begged, others wouldn’t react cruelly, forgetting the humanity in front of them. Keba grounds this belief in his own childhood. Despite their circumstance, his mother never resorted to begging for food or clothes for her family. She worked and she relied on what she was given.

Keba takes his mother to be the standard for all suffering from poverty. He looks into his past, blindly snatches the actions of one woman from the perspective of her young son, and stretches it so that it will fit the context of his adulthood without regard to changing times and the circumstance of different people.

My response mimics the effects of Keba’s actions. His interpretation of his memory is a broken mirror, showing him a reality in different angles depending on which perspective he wishes to address. In the center is the word ‘selflessness,’ which gets distorted as it meets an edge. Part of the ‘f’ dissipates away, and the end of the word, when it travels to the next pane, is magnified in a way similar to how I imagine Keba may have magnified some actions or glossed over others.

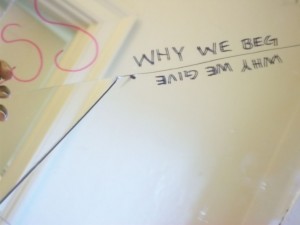

I split part of a quotation that seems to be the essence of Keba. He says to his secretary on the topic of beggars, “Don’t you realise that everything separates me from them! Poverty has never compelled people to beg; poverty has never excluded self-respect, human dignity!” (Fall 44) This excerpt shows Keba’s reconciliation of himself as a boy and the poorest people in the city. I think he could be more at peace with his past and present and those around him if he readdressed what dignity looks like, where it comes from, and which human has the power to take it away.

The trouble comes in when look at the crux of the givers and receivers. Fall’s beggars believe “That’s what religion says: when we beg we just claim what is our due!” (Fall 61) And they believe that people “given out of an instinct for self-preservation” (Fall 22). And with the exchange of blessings for sustenance, the beggars are satisfied, yet Keba does not see it this way. He doesn’t comprehend the intrinsic dignity of a person given by God and unaffected by the actions of any man.