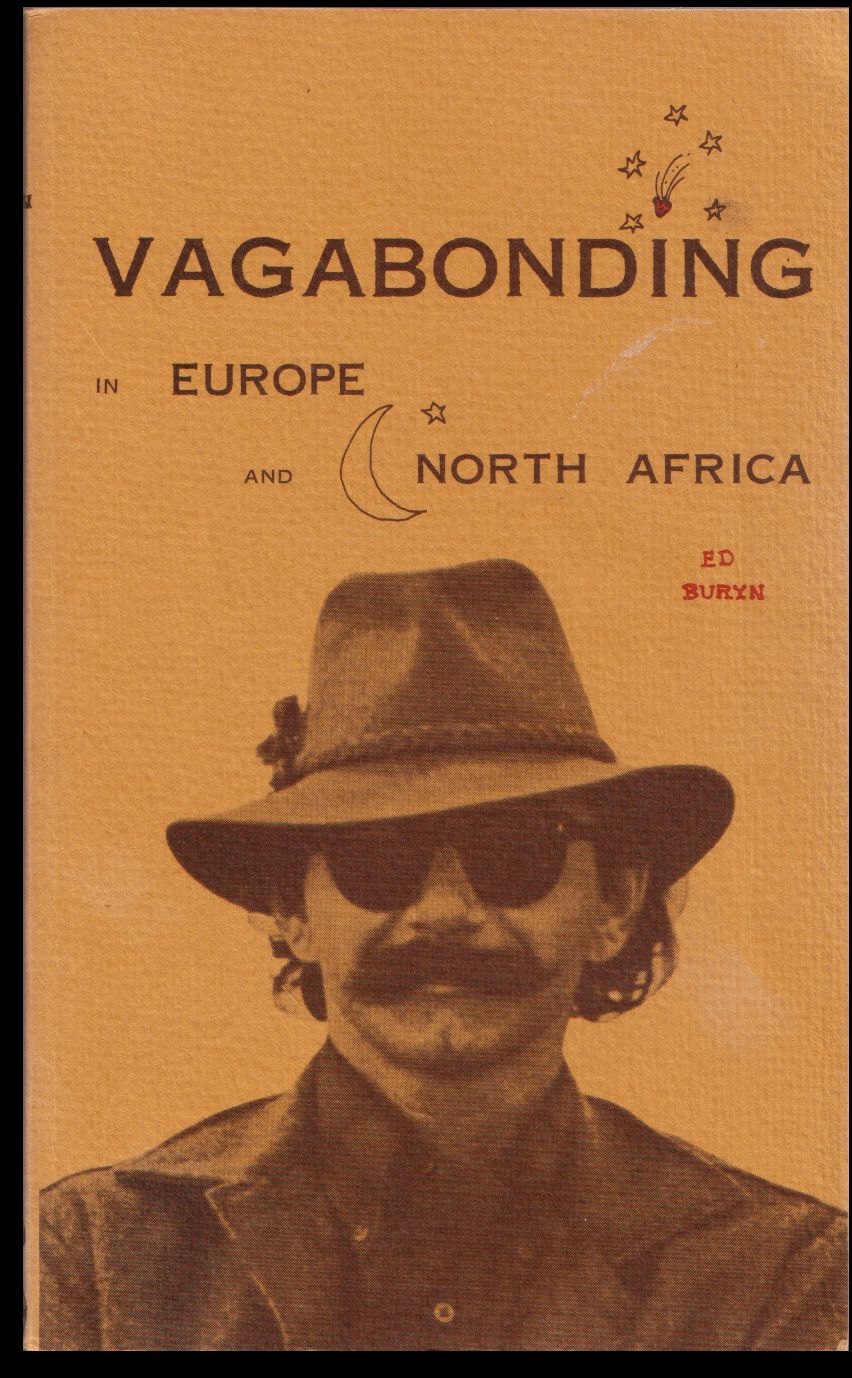

I think Ed Buryn’s term, “vagabonding” has a nice ring to it, but it never really took off; Europeans tend to call it “backpacking” but that means wilderness travel to me. Formally, you might call it “independent travel” to distinguish it from packaged tours and the like but independent travellers have been around forever and that doesn’t really catch the sense of it.

I’m thinking more specifically of the young kids from Australia and Denmark and Israel and Japan an d even the US who drop out for months or years at a time to travel all over the world, on the cheap. They stay in youth hostels in big European cities and crummy motels on Khao San Rd. in Bangkok and take overnight buses to distant beach towns on the promise of full moon raves and they stink of patchouli and worse. I have often said that when I die and go to hell there are going to be a couple of German hippies there with dayglo backpacks complaining about the room rates.

d even the US who drop out for months or years at a time to travel all over the world, on the cheap. They stay in youth hostels in big European cities and crummy motels on Khao San Rd. in Bangkok and take overnight buses to distant beach towns on the promise of full moon raves and they stink of patchouli and worse. I have often said that when I die and go to hell there are going to be a couple of German hippies there with dayglo backpacks complaining about the room rates.

Whatever you call it, Lonely Planet has played an instrumental role in the evolution of the hippy trail over the past thirty years. They are the main source of documentation on this essentially grassroots movement. There is no corporate sponsorship. Vagabonding is not written about in the travel section of your local newspaper or in Conde Nast Traveller or your inflight airline magazine. This travelling phenomenon predated Tony and Maureen Wheeler, and they have only chronicled parts of it in their iconic guidebooks, but they’ve done so in such detail and for so long, and without real antecedents, that it’s hard to imagine life on the road without LP. Ed Buryn’s Vagabonding pre-dated the Wheelers’ efforts, but his was more of a musing on the art of travel and less of a practical guide, and in any event he didn’t follow up with more and more and more guides so that eventually you had not only a Lonely Planet India but a Lonely Planet Trekking in India and a Lonely Planet Goa and so on and on. In many parts of the world, there are better guidebooks, and there are few places where there aren’t at least alternatives to the Lonely Planet offering, but LP still, after all these years, retains enough authenticity and authority that it’s probably the default choice for independent travellers in most of the world.

And in some places, like Burma, it’s really the only choice, and you can see how influential the Wheelers’ little publishing empire really is. I don’t think that it’s an exaggeration to say that most travellers to Burma see the country through the eyes of Tony Wheeler. (He wrote parts of the Burma book himself, but by extension this is true with the rest of the catalog.) The literature on Burma in the west is pretty thin; what people know about Burma is largely what they read in their guidebook. And where they go is where their guidebook tells them. Now, it’s worth debating whether the guidebook is following the hippies or the other way around. I suspect that in many places the hippies came first. In Burma, I’m not so sure.

But in either case, one interesting characteristic of this understudied phenomenon is how regularized it is. One of the original hippy trails, the one that the Wheelers travelled before they wrote their first book, Across Asia on the Cheap, went from London via Istambul and Kabul to Kathmandu. Now, of course, that route is no longer possible, although Tony Wheeler, bless his heart, is working on a new edition of Lonely Planet Afghanistan. But the same places — the Thamel hippy ghetto in Kathmandu, for example — that were on the trail thirty years ago are still there. Bangkok is a big bustling dynamic city, but the little hippy ghetto there, Khao San Road, has likewise remained intact over the years. I haven’t been to Istambul but I would be willing to bet that the same dynamic has occurred there; I used to know the name of a restaurant that “everyone” went to in Istambul, even though I’ve never been within a thousand miles of the place. Hippies pick nice places, as Buryn observed. It should be a formal rule, “Buryn’s Rule”, from page 197 of the first edition of Vagabonding: “hippies do have excellent taste in selecting places to hang out.”

And for routes that are still possible, the independent travellers follow them with a consistency that would imply more formal organization. Anyone who has travelled like this knows what I mean: you end up in the same hotels in the same cities with the same people, hundreds of miles and weeks apart. It’s like being on a packaged tour without a guide. I know that you weren’t like that, but all the others were, right?

Now, the analogy is not exact, but there are interesting parallels between this independent traveller phenomenon and the open source movement, especially in the role that Lonely Planet and O’Reilly play. You wouldn’t think, at first thought, that books would be all that important in either case, especially in software. But a quick glance at my bookshelf yields Garfinkel’s PGP book, an old copy of Unix in a Nutshell, Peter Morville’s Polar Bear book on Information Architecture, the Camel book (Perl), a book on UML, and a couple of others — all from O’Reilly. And I’ve got probably two dozen Lonely Planet guidebooks, including a couple (Bushwalking in Papua New Guinea?) that were more aspirational than useful. Well, come to think of it, you could put the Perl book in that category too.

O’Reilly, like Lonely Planet, has played several roles in their (open source) community, first as documentarian and later as distiller and promoter of trends. O’Reilly books and conferences — and even, briefly, software — have been focal points for open source software. Open source would have happened without O’Reilly and it’s useless to speculate how it would have been different, but I think it’s worth noting that their books have been guides to Perl and Linux for open source hackers in very much the same way that Lonely Planet’s books have been guides independent travellers in Yunnan and Baja California.

Both O’Reilly and Lonely Planet carved out a profitable niche selling guidebooks to a chaotic and unstructured, but obviously underserved, market and each helped to define or describe those markets (or movements) through their guides.

Neither the open source movement nor the vagabonding movement are formally organized but they both show signs of complex, emergent patterns, like slime molds or the organization of cities themselves. They both also have clearly defined ideals and social mores, shared senses of group identities, and common enemies. Even though neither group is uniform — they’re both really groups of groups of groups — they’re clearly distinct, with regular patterns of behavior.

They’re both grassroots systems, occasionally idealistic, and young. Both have necessary pragmatic streaks: you have to cope for yourself on the road and you have to write good code yourself in the open source community. I don’t want to extend the analogy too far because they are not that closely related; but I think it is interesting the parallels between the two book publishers, Wheeler from Lonely Planet and Tim O’Reilly from O’Reilly Media, at the center of both phenomena.

d even the US who drop out for months or years at a time to travel all over the world, on the cheap. They stay in youth hostels in big European cities and crummy motels on Khao San Rd. in Bangkok and take overnight buses to distant beach towns on the promise of full moon raves and they stink of patchouli and worse. I have often said that when I die and go to hell there are going to be a couple of German hippies there with dayglo backpacks complaining about the room rates.

d even the US who drop out for months or years at a time to travel all over the world, on the cheap. They stay in youth hostels in big European cities and crummy motels on Khao San Rd. in Bangkok and take overnight buses to distant beach towns on the promise of full moon raves and they stink of patchouli and worse. I have often said that when I die and go to hell there are going to be a couple of German hippies there with dayglo backpacks complaining about the room rates.