Post #4: Heavenly Prototype

March 20th, 2018

The fourth, final, and most dramatic track of my mini-album, “heavenly prototype,” can be heard at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/track/heavenly-prototype

I am particularly excited about how this song turned out. It is just short of 9 minutes long, and is fairly packed with numerous thematic elements. I’ll do my best to break it down as concisely as possible.

First and foremost, “heavenly prototype” ultimately engages with one question: How do we, the humans who are so inclined to forget God and God’s word, interact with and understand that word in our lives of faith(s)? The central image, from which the song gets its name, is the Umm al-Kitab, the “Mother of the Book,” otherwise known as the “heavenly prototype from which all scriptures come” (a quote from my lecture notes). This book is referred to in the song as “the heavenly prototype,” “our mother book,” and “the book above.” The first lyrical section of the song is concerned with Creation, and I connect the idea of this eternal, ever-writing book to what Nasr calls “the Primordial Word,” the original word that began the process of creation, and the “Divine Pen” (al-Qalam) which writes “the realities of all things” (Nasr 17). The Divine Pen is present (referenced as simply “The Pen”) throughout the song, and continues to write constantly in the language of God’s love.

How does that heavenly word get to us? I touch upon this in the song also. Way back at the beginning of the course, we discussed “Incarnation” and “Inlibration” (Word Made Flesh, Word Made Book, Lecture on January 30), and how the Word in Christianity is manifest in Jesus, whereas the Word in Islam is manifest in the Qur’an (which, as Sells points out on page 4 of Approaching the Qur’an, is why the parallel is not as strong between Jesus and Muhammad as it is between Jesus and the Recitation itself). The Word becomes manifest for Christian in Jesus (who “walks,” as I say in the song, with reference to Jesus’ adventurous traveling mystery), whereas the Word in Islam is manifest in the recited Qur’an (as I sing, “and Muhammad talks,” in reference to recitation, and also as a nod to Lupe Fiasco’s song about the Prophets). These are some ways that the Word, ancient and divine, gets to us, the young and God-forgetting humans. I make sure to mention both Jesus and the Qur’an as a way of remembering how the Heavenly Prototype is supposed to inform the scriptures of all the People of the Book, not just the Qur’an.

But what we do with the Word when we receive it through some kind of manifestation is not always as holy as the Word itself. This is the musing of the chaotic climax of the song, in which I lament that while the Word is a Word of love, it comes to us through different religious traditions (whether incarnated or inlibrated) and is twisted by some of us. It can be forged into a weapon, or a tool of oppression. As myriad interpretations of the Word arise in diverse religious traditions and sub-traditions, conflict is created. We disagree about the Word, we interpret it differently in different communities–this is exemplified by the chaotic instrumental that builds up halfway through the song. While the chaos is sometimes indicative of actual bloody or bigoted conflict, I think it also can simply reflect the sheer extent of the multiplicity of interpretations, on a scale which is difficult to wrap one’s mind around (generally, I’m influenced by the course’s cultural-studies approach when thinking about this. Different Islams, different Christianities, etc. all cry out in different ways during the chaotic sonic climax that makes any clarity or continuity harder to discern).

However, it ends on a peaceful, hopeful note, with quiet ambient instrumental and a meditation on how the divine Word itself, written by that Divine Pen, is so much more enduring than the petty hermeneutical conflicts we perpetuate with each other; God has the final Word, and thankfully, Creation can never be completely separate from it (Every leaf is a page of sacred scripture, to reference a Saadi line we discussed in class). Therefore, the trajectory of the song is meant to reflect the trajectory of the Word and the Heavenly Prototype as it is presented. It begins in peaceful ambience with the blissful institution of Creation by God, and then follows the Word as it is given as a gift through different scriptures and traditions to mankind, and then bastardized or confused by competing communities of interpretation, reaching an almost jarring sonic climax, before ending again in the peace of Divinity, the peace which the true Word always had since Creation began, the peace that defines the Heavenly Prototype even as all earthly scriptures face problems of interpretation. There is therefore ultimately a hope in God and God’s Love present at the end of the song, and I think it’s a fitting way to end the mini-album.

I really hope you enjoy these music pieces as much as I enjoyed composing and recording them!

Post #3: Love on Moth’s Wings

March 20th, 2018

The third and title-track of my mini-album is called “love on moth’s wings,” and can be heard at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/album/love-on-moths-wings

(As with previous posts, the lyrics are found in the link).

In Week 7 of AI54, we examined various local kinds of devotional music. One example of this was a Ginan entitled “Hu(n) Re Peeaassee.” A ginan is a devotional hymn sung by members of Ismaili Shi’a communities in South Asia. When Professor Asani played a recording of an arrangement of “Hu(n) Ew Peeaassee” in class and showed us a translation of the lyrics, I could not believe how much I was moved by the words. I have long been in love with the mystical aspects of my native Anglo-Catholic Christianity, and to encounter mystical language from a different tradition that, while employing different vocabulary, nevertheless express the longing for unity with Divinity that I feel very strongly was a wonderful experience.

I greatly appreciated the lyrics of “Hu(n) Re Peeaassee,” and wanted to interact with them somehow by creating devotional/mystical music of my own. The result is this song, “love on moth’s wings,” a folk-inflected dream-pop ballad about the surrender of the self and the longing for the truest knowledge of God: Unity through Love. The lyrics of “love on moth’s wings” are perhaps best described as an augmented paraphrase. The verses borrow language directly from the Ginan, and the first line (“I thirst, O Beloved, for a vision of You) is a direct quote from the translation. As Asani points out in Chapter 3 of Ecstasy and Enlightenment, a central facet of this South Asian Ismaili music is the imagery of “spiritual marriage” and the language of the woman-soul (Asani 55-57), and I did my best to preserve this throughout my piece, particularly in the moments when I meditate on humility and self-sacrifice (as the Ginan says, “it is by becoming nothing that one is called a handmaiden”).

I note that in Ginans, just as a general mystical experience is often described, so also is a relationship between the disciple of the Ismaili Imam (the murid) and the Imam himself (Asani 57). I concede that this is downplayed slightly in my own synthesis of the Ginan’s lyrics; considering the choruses I composed to supplement the verses, I think the song has turned out to be an expression of longing for oneness with Divinity more than longing for spiritual marriage to a human religious leader.

I really dug into the animal imagery found in my favorite stanzas of the ginan: the displaced fish, the greedy bee, and most importantly, the moth that gives of itself, diving toward the light in an act of sacrifice. These creatures pop up in the second verse of “love on moth’s wings,” and the moth becomes the enduring, ideal image which I long to emulate for the rest of the song, as I “tumble toward the light” in an act of self-giving sacrifice to attain unity with the Beloved. The last line of the song evokes some more of the romantic/marriage language, at least implicitly: “I want to be yours.”

The first chorus is a product and description of my own contemplative prayer practice, which seeks the silence of unknowing to find the Unity with the Beloved that the ginan describes. The second chorus, while embellishing on the moth imagery present in the ginan, also evokes imagery of my favorite poem by Rumi:

I connect this falling which produces wings to the moths who sacrifice themselves for the sake of the light and for unity with the beloved in the ginan (“these fluttering broken beings who in honest falling find true wings, and through the door, love”). I really hope you like this song!

Post #2: Isa and the Dead Dog

March 20th, 2018

The second song on my mini-album is called “isa and the dead dog,” and can be listened to at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/track/isa-and-the-dead-dog

(Also, the links also include a transcript of the lyrics of the song, so you can follow along with my language as you listen to the music).

In week 3 of the course, specifically on February 8, we discussed the role of Prophets in the Islamic tradition. We learned about how Muhammad is himself one of many Prophets (though, according to some Muslims, he is the last one). Many of the venerated Prophets in Islam are spiritual heroes shared with pre-Islamic tradition: Jewish figures such as Ibrahim (Abraham) or Yusuf (Joseph) or Musa (Moses), or Christian figures like Yahya (John the Baptist) or, most importantly for this post, Isa (Jesus). Prophetic stories have been prevalent in Islam since the inception of the Qur’an itself. The Qur’an highlights the presence of prophets in numerous religious traditions (see Suras 3:8, 10:47, 35:24, 4:164, 10:94, and also the miraculous Qur’anic retelling of the story of Joseph found in Sura 12 for examples). As the tradition has developed, prophetic stories have become their own genre, and are wonderful pedagogical tools for demonstrating the ways in which the Prophets are imitable paragons of virtue and righteousness.

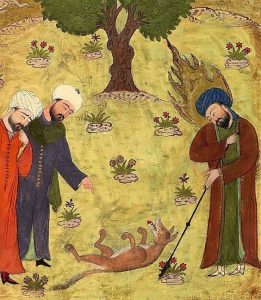

In week 3, my favorite example of a prophetic story that we learned was the story of Isa and the Dead Dog. As a devout Christian, it was great fun to see Jesus manifest in a refreshing way in another tradition! Professor Asani began his account by showing us this picture:

He told us the story: Isa was walking with his disciples when they came upon the corpse of a dog. The disciples ranted about how ugly and smelly the dead dog was, but Isa knelt down beside the dog and, ever seeing the divine beauty in all things, proclaimed that the dog had beautiful white teeth. What a lovely little parable!

For the second song of my mini-album, I attempted to retell (and also expand) the story of Isa and the Dead Dog. As it is a rather bizarre story, I tried my best to make the song a bit odd. The drum beat has a slight swing to it, and the piece features some synthesizer work that I think adds both beauty and idiosyncrasy (the story itself is both beautiful and idiosyncratic). The lyrics themselves add to the bizarre quality of the piece–I’m singing about Jesus and I’m singing about dog corpses, hardly a classic combo–but I think they’re a lot of fun! The first verse and chorus simply retell the story from the perspective of Isa’s disciples: they see a dead dog, and are astounded by Jesus’ ability to see beauty in the dead dog.

Then, I try to expand the parable and get at some possible ramifications for us, as people. What does it teach us about how God looks at humanity? What does it teach us about how each of us should view the world? With the second verse and last two choruses, I begin by asking the question, “Am I a dead dog?” (A metaphor, obviously). If I am a dead dog, then perhaps the Prophet Isa would still see the beauty in me, despite how very far I have fallen, despite how ugly the rest of the world thinks I am. Perhaps God feels the same way. Isa is a Prophetic paragon of virtue in this story because he imitates the Divine by seeing the inherent beauty and goodness of all created things, and as with all Prophets in the Muslim tradition, we would do well to learn from him.

Post #1: Basmala

March 20th, 2018

What a pleasure it has been to engage with all the materials of our course thus far! I am so excited to share that, for my first set of blog posts, I have produced a mini-album of original songs inspired by various aspects of the course material. The entire mini-album is called “love on moth’s wings” (for the record, I tend to avoid capital letters in my song titles and lyrics), and all four tracks can be found at this link:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/album/love-on-moths-wings

But, for ease of access, for each individual post, I’ll also include a link to the individual song about which I’m writing. The first song, and first post, is called “basmala,” and can be listened to here:

https://oakwool.bandcamp.com/track/basmala

“basmala” is an ambient folktronica song featuring a simple chord progression and one lyrical phrase, the Basmala (“bi-smi llāhi r-raḥmāni r-raḥīm,” a phrase which I have learned has myriad translations. I chose to work with one I heard in class and saw on the course website, “In the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful), followed by an “Amen.” The Basmala reminds me of a prayer from my own tradition, the trinitarian formula (“in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit”) because of its versatility. Just as the trinitarian formula is used in all kinds of prayer circumstances in Christianity, both private and corporate, so too does the Basmala have variable uses. As I have seen in my examination of the Suras, almost every one begins with the Basmala (in the Michael Sells translation which we have examined for class readings, the translation is slightly different: “In the name of God the Compassionate the Caring”). Beyond Qur’anic use, we have seen how the Basmala permeates Muslim cultures. It is repeated prominently in daily prayers, featured prominently in Islamic calligraphy, and even manifests in the constitutions of many countries where Islam is the official religion. Nasr’s book, Islamic Art and Spirituality, which we read for class, begins with the Basmala.

I appreciate how the Basmala is made manifest in manifold contexts. This reflects that, for many Muslims, God consciousness is not only to be maintained in scripture itself or in corporate prayer. All endeavors may happen in the name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. This of course includes prayerful activities. As I recorded the other songs for my mini-album, I realized that I too was participating in an act of prayer, and so I wrote “basmala” to be the first track, to dedicate the whole album to the name of God and to reflect the prayerfulness of the art that I create. As Nasr writes, “Islamic art is the result of the manifestation of Unity upon the plane of multiplicity” (Nasr 7). Though I am not Muslim in the modern, ideological, categorical sense of the word, I do believe I am a lower-case “m” muslim in the Qur’anic sense of the word, in that I try my best to submit to the will of God (Asani, Infidel of Love, 28-29). Therefore, I hope that in some small way my art can contribute to the multiplicity of artistic manifestations of divine Unity, and so I begin it with the Basmala.

The last thing I’ll comment on is the structure and style of the song itself. It is supposed to evoke relaxed, peaceful feelings, setting a prayerful, reverent tone for the album (I wanted its sound to reflect the lyrical role this song plays, and so I went for an ethereal, heavenly, and mystical sonic quality, with soaring reverberations and ambient spaciousness). The listener will also notice that as the song continues, more instrumental layers build up and more voices are heard. This growing chorus of singers and instruments is intended to reflect how, while the song is an individual articulation of the Basmala, all things in Creation are ultimately expressions of Divinity–God communicates through Creation, and suffuses Creation with “divine signs” (Renard, Seven Doors to Islam, 2)–and so all things Created sing together: In the Name of God, the Compassionate, the Merciful. Amen.