Introductory Essay

ø

An Islamic Self-Portrait

My pieces come together to represent an immigrant-based view on Islam. The pieces do not have a cohesive cultural or religious theme. Instead, they demonstrate a conglomeration of snapshots, sometimes competing with and sometimes complementing one another. Placed together, the six works aim to capture the tensions and nuances of growing up Muslim in a non-Muslim country. In short, this portfolio is an immigrant Islamic self-portrait. This essay will first begin by discussing major themes of the course and how they shaped my conceptualization of the Muslim identity. It will then focus on key theoretical components and their contributions to this essay’s focus on Muslims living outside Islamic countries. Finally, the essay will proceed chronologically through the six pieces, introducing and contextualizing each work by elaborating on its significance within the portfolio as a whole. This essay aims to show that each Muslim community has a distinct identity. It hopes to introduce the American-Muslim experience not as a derivation of one of the many Islamic traditions, but instead, as a unique religious culture in and of itself – one that faces its own distinct internal and external pressures.

Part I: Course Themes

The course began with a general discussion of Islam and its core principles with an experience-based orientation instead of a legalistic one. From the first lectures, Islam was not presented as a strict doctrine, but rather as a set of beliefs manifested through oral, calligraphic, and community-based traditions. For me, Islam went from being an individual-based religion (one that emphasizes a person’s relationship with God alone) to a community-based religion (one that believes in bringing people together to honor God). Islam is often experienced alone, either on a prayer mat or with a Quran. By focusing on how the Quran was originally shared orally and not through text, the Islamic emphasis on shared experiences became clear. Seen this way, communal practices like Friday prayer are not an exception to the otherwise individual-based religion; instead, they are the focus of Islam.

The course then moved to the development of the two major Islamic sects: Suni and Shi’a. Following the death of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), Muslims disputed the rightful successor to the ummah. Sunnis believed that the prophet’s (PBUH) close companion and a preeminent Islamic scholar, Abu Bakr, was the rightful caliph. Shi’a believed that the prophet’s (PBUH) cousin, Ali ibn Abi Talib (and later Ali’s children Imam Hasan and Imam Husayn) was the legitimate leader. At the core of this dispute is a disagreement over religious legitimacy. Does Islamic authority transition through legal knowledge or through charisma? Should the leader of the ummah be chosen based on their background in religious texts or based on their relationship to the prophet (PBUH) (implying a level of divine lineage). Additionally, by learning about the Battle of Karbala in a classroom setting, I understood the long-term philosophical differences that developed over the military encounter. Sunni have interpreted Islamic strength through political power ever since the prophet (PBUH) won the early battles against Quraysh and Yazid I triumphed over the Shi’a in Karbala. Shi’a on the other hand have understood Islam as a religion of perseverance and steadfastness. Political power does not equate religious strength. Not only did this unit develop my understanding, and therefore appreciation, of Shi’a beliefs, it also made me reconsider my Sunni identity and religious beliefs more critically. I walked away from this part of the semester understanding that even Islamic leaders did not go uncontested. Disputes over Islamic legitimacy are not a recent phenomenon. The Sunni viewpoint is only one way of seeing religious authority in Islam. The religion is not contained to knowledge of the doctrine.

While Shi’ism broadened my understanding of religious authority, Sufism introduced me to a new conception of Islam entirely. I have always understood Islam through the legalistic approach that puts the Quran and the hadith at the center of the faith. Sufis however have a different orientation towards Islam. One becomes closer with God not by becoming closer to his texts; instead, a closer connection is built through love. Ishq majazi (human/worldly love) is seen as a step towards Ishq haqiqi (true love of God). Sufism sees love as a facilitator for people to transition from the zahir (external) to the batin (internal). Within this context, Islam became a much quieter force. One identifies powerfully with Islam not through adherence to religious codes but through the development of a deep, loving connection with God. The material on Sufism made Islam a much less bounded and much more forgiving religion. Faith is much more fluid than the five pillars.

The course ended on the reformist/revivalist Islamic movements. Following the Great Western Transmutation where political power shifted from the Islamic World towards the West, Muslims entered a period of religious crisis. They saw the shift in power as a representation of weak faith. As a result, they interpreted global politics as a sign that Islam had to be reinterpreted either by reforming contemporary beliefs or reviving the tradition of the prophet (PBUH). This anxiety manifested itself in a number of different movements. We discussed the conservative (continues to interpret Islam according to the Sunni scholars: Hanafi, Shai’i, Maliki, Hanbali), back to the fundamentals (reorientation towards the prophet’s (PBUH) actions instead of the Sunni scholars’ interpretations), imitative (the recreation of Western religion-state relationships in the Muslim world), adaptationist/integrative (the integration of Western models in an Islamic framework), and Islamist (the adoptation of Islam as a political ideology by a nation state) frameworks. We also saw Nationalism and transnationalism (pan-Islamism) as vehicles to vocalize religious sentiments. This unit was a familiar topic for me (the politics of Islam) but with a new background in the Islamic tradition. With greater understanding of Sunni, Shi’a, and Sufi beliefs, I had a greater appreciation for the disputes on the co-optation of religious authority by various groups.

For me, the course culminated in one of the final readings: Hanif Kureishi’s “My Son the Fanatic.” The protagonist, a young Pakistani growing up in the West, has a difficult time bridging his identity as a foreigner both in the U.K. and in Pakistan. When he visits Pakistan, he does not feel like he can relate to the religious traditions there. To complicate matters further, the protagonist appears to appreciate a third culture’s Islamic community more than the cultures in either of his other identities. He has posters and reads works by African-Americans: Elijah Muhammad, James Baldwin, Malcolm X, and Muhammad Ali. The protagonist relates to figures that are neither from the U.K. nor from Pakistan, but rather African-Americans growing up across the Atlantic. This reading was meaningful for me because it showed the impact of globalization on Islam. If there was diversity in the Islamic tradition before, the increased access to information has made it even easier to question, critique, and adopt new Islamic beliefs than ever before. This feels pertinent to my experience growing up in America where there is a particularly wide variety of Islamic beliefs shared among even my closest friends. The second part of this essay will apply the themes introduced earlier to my portfolio within the context of my experiences as an American-Muslim.

Part II: Personal Narrative

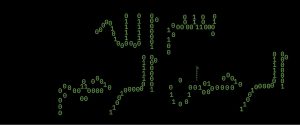

The first piece emphasizes the importance of science in the Islamic tradition. Oftentimes, especially being educated in a secular context, I have been taught that Islam is antithetical to modernization and scientitific development (a theme that I continues even in my GOV20 class at Harvard for cultural theorists like Samuel Huntington and Max Weber). Islam is seen as a rigid faith that imposes harsh, conservative religious doctrines that stand against scientific development. My first piece was in large part a reaction to the first unit of the course. Islam is not appreciated only through readings of the Quran and hadith. It can be experienced and felt in daily actions and beliefs. A person’s drive to learn, even if it is not directly related to religion can have deep religious underpinnings. In this piece, I have repurposed the traditional Islamic abjad numeral system and combined it with the scientific binary system. The piece shows how Islam is not just a rigid legal code, but rather, an animated religion that continues to adapt and motivate its adherents to explore.

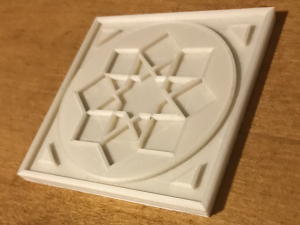

My second piece responds to the Shi’a literature that I read in class. Having learned about the Shi’a experience of Islam through loss, I used an example that I learned as a child in which the prophet’s (PBUH) life was at risk and he had to persevere. By focusing on his message to Abu Bakr that he should not be sad because God is with them allowed me to connect my own experiences and understanding of Islam to the Shi’i interpretation. I remember visiting Dearborn, Michigan as a young child and feeling that I did not understand the religious symbols, figures or history that the city’s Shi’a population used in their stores. The Shi’a tradition felt very distant to me. This piece allowed me to bridge that gap and see the Shi’a interpretation in my own conceptualization of Islam. Piece 3 served a similar purpose in allowing me to create an Islamic object that felt like my own by virtue of the religious significance I see in it (rather than the inherent religious value it carries).

Pieces four and five were motivated by the broadening of my interpretation of what constituted an “Islamic culture.” Through my experiences in Islamic sunday schools, I had only seen Islam as a study of the Quran and its recitation. Culture and religion were separate. This course, especially the weeks on Sufism, has shown me that this is not true. I learned that religion is an experience; therefore, one’s encounters with religion are defined by the culture one lives in. The fifth piece shows how Islam can be approached from a variety of angles and that the purity of the faith can be found in all traditions whether it is Shi’a, Sunni, or Sufi. This also reshaped my understanding of what it means to be Muslim in America. There is not one single religious interpretation that I have to adhere to. The religion is fluid and dynamic. My cultural surroundings are an important part of how I experience the religion; they do not have to be removed for me to feel like a true Muslim or for me to be a part of the “True” Islam.

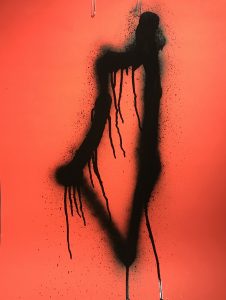

The sixth piece made the conversations about reformist and revivalist movements personal for me. It related the theory and case studies back to my Palestinian identity. “My Son the Fanatic” played an important role in encouraging me to design this piece. I felt that even though I am a Palestinian, I do not have to necessarily buy the Islamic interpretations supported by some groups in Palestine wholesale. At the same time, as an American, I do not have to subscribe to the secularity of the West. It is possible to juggle two religious identities at the same time and identify with neither or both. Although the sixth piece makes a statement about Palestine, within the context of the portfolio at-large, it makes a second point about what it means to be both Palestinian and American without adopting either society’s view on religion whole-heartedly. This does not suggest that I have come to some sort of resolve on my Muslim identity. The final piece actually does the opposite. It shows that my understanding of Islam continues to be dynamic and malleable as I nuance my Islamic self-portrait.

Sources:

Asani, Ali. “Reform and Revival Movements” Gened 1087, 7 Nov. 2019, Harvard College.

Hanif Kureishi, “My Son the Fanatic,” in The Post-colonial Question: Common Skies, Divided Horizons, eds. Lain Chambers and Lidia Curti (London: Routledge, 1996), 234-241.