(or, Simulating a Simulation)

This is the second post in a series on teaching about games in higher education. See also: the first post (Writing the Casual Games Syllabus).

As you’re making your way through the end of the first level of Bioshock [2007] (one of the most critically-acclaimed video games of all time and one that defined its own genre: objectivist FPS), you’ll be abruptly trapped in a small room when your enemy (Atlas) slams a remote-controlled door.

The lights go out. (Dramatic!)

Through a wall of safety glass windows, a television monitor lights up and delivers a preening speech from your antagonist–a speech worthy of a James Bond super-villian in a closing scene. He says:

So tell me, friend, which one of the bitches sent you, the KGB wolf or the CIA jackal? Here’s the news: … Andrew Ryan isn’t a giddy socialite who can be slapped around by government muscle, and with that, farewell, or Dasvadinya -– whichever you prefer.

At the speech’s conclusion, a gang of “splicers” (think: zombies) runs up to the other side of the safety glass and starts pounding on it and screaming. (Very dramatic!) You’re still trapped in the room, and if it is your first play-through you probably don’t want to fight this mob.

Then the glass starts to crack. (Ultra dramatic!)

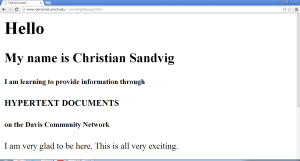

They’re breaking through! in BioShock [2007]

(Click to enlarge.)

When I played this, I frantically searched for something to do. I guessed that the game wouldn’t kill me outright at this point… but who knows? So it was with a rising sense of panic that I scoured the walls, desperate for a tooltip, for escape, for anything.

Luckily, just as it felt like the splicers would break through, the sometime-ally and narrator (Atlas) managed to open the locked door of my trap by radio or something and I was free to run away. Whew. That was close.

But was it close? If you stay in the room you’ll quickly discover that the whole thing was a sham of interactivity. The door opens on a timer. The splicer/zombies never break through the glass. They’re on a short loop of repeated banging and screaming that it is easy to see, if you stand and look. It’s actually a cut-scene disguised as gameplay.

It’s the same situation in State of Decay, the open-world zombie apocalypse survival game that has broken all sales records since its release on Xbox 360 arcade last June. It is an excellent game that has also reviewed well. I evaluated it for my Play and Technology syllabus (see the last post). I like the game, it is a terrific achievement.

State of Decay logo [2013]

Why are people excited about it? It gets a lot of credit for emphasizing gameplay as opposed to wordy narrative (cf. The Last of Us and The Walking Dead [The Game]), and many reviewers have praised the basic concept of a “zombie survival sim.” As Tom Chick writes in praise of this game at Quarter to Three:

The best type of storytelling in a videogame is the type of storytelling that makes videogames unique: me in a sandbox of possibility, making stories out of my own choices.

I agree! Sounds great!

Also, the idea of a “zombie survival sim” is itself an achievement. Simulation is a fascinating and important topic in relation to games. So, I thought: Why not teach about simulation with a zombie survival sim? Seems like a novel approach that would usefully get us away from SimCity. And State of Decay looked good — in the words of the producer, “The game is basically a giant simulation.”

Forget SimCity — there’s no tame discussion of municipal zoning rules here! State of Decay [2013] (Click to enlarge.)

Certainly everything else in State of Decay isn’t novel. Every concept in there is ripped off from some other zombie media franchise, sometimes with a wink (Twinkie snacks! Rule #1: Cardio!) and sometimes not. The achievement here, as is true for many other popular games like Grand Theft Auto, is really in execution — bringing together a lot of things that have existed in games before, but getting them to work well together.

As I eagerly waded into my second play-through, I hit a speed bump. After a while, my ally and narrator Lilly told me: “I really don’t think we should be getting into bed with the Wilkersons.” She goes on in this vein for some time.

For me, this was a jarring bit of NPC dialogue.

Wait, I thought, I just told the Wilkersons to go to hell! Doesn’t Lilly realize that?

Unlike my first play-through, I had done everything possible to be against the Wilkersons. I was the anti-Wilkersons. Yet Lilly’s dialogue was the same as in my first playthrough, when I was pro-Wilkersons. As I was puzzling over this, the Wilkersons gave me some gifts. It seems like the story in “State of Decay” is continuing on without me at the helm.

At first I thought this surprising non-interactivity only applied to the hypertext, or what gamers call the “story line missions,” but I was surprised to find that the enforced linearity of the plot also applies to the open world elements and the simulation components as well — in a very ambitious way.

In a sentence, this game is presented as Night of the Living Dead meets Lemonade Stand. Check out the resources screen:

Here’s part of the map:

So far so good, right? Any sim gamer is drooling, let me assure you. It screams, “sim! sim! sim!”

Here are the stated rules if you care for that sort of thing.

In State of Decay’s “apocalypse survival simulation,” you control a band of survivors (the community). You can locate them at any of eight home sites on a large map, which you must defend against zombie hordes. A game day is represented by two real-life hours (one daylight, one night). Each game day your group uses some of five basic resources: food, ammunition, medicine, building materials, and fuel.

You must loot buildings to find these five basic resources, and can construct some of nine facilities at your home base that modify your use of the resources. There are also other groups of survivors who have their own home bases, and they will potentially trade resources with you, or join you. The zombies also have home bases (called infestations) that spawn zombie hordes. You can build “outposts” that eliminate hordes, or you can destroy zombie home bases (infestations) but they will randomly recur.

A few more details: Each day, there is a chance that a member of your community will fall ill, go missing, throw a tantrum, or even be killed. You can potentially recruit neighboring survivors or strangers you encounter to join your group to make up any losses. A variety of other things are also tracked: the morale of your group, your group’s reputation with each individual neighboring group, your community’s overall renown in the game world, and more.

It’s a great formula, I’m itching to play it. Because, you see, I thought that I was playing it when I played State of Decay but it turns out I was not. Most of the information in the box above comes from in-game dialogue and explanatory text. And it’s mostly false. The game told me that was how the simulation worked, but how does it actually work?

Let me show you:

In the game, Sgt. Tam told me to “stockpile resources” — now I see why the NPCs have to say these things because it actually doesn’t matter if I stockpile them or not. It’s not just that these are score points with no consequences, they aren’t even score points as they are disconnected from my actions. It appears to be impossible to deplete some of the resources very much. I decided to not collect any resources at all and learned that resources can vary in a manner that I experienced as random. Some of them will decrease to zero, but when they do, no one even mentions it. Then they’ll go back up as the NPC gather them for you.

The game pop-up warns me that “Morale is low.” But so what? I dropped it to zero and I could not detect any consequence. If anything, game messages like “Grady is sad” appeared more often when my morale was high. Running out of food entirely for a long period produced a modest stamina penalty for 2-3 of my team members (“Grady is hungry”).

The premise of the game is that I have to defend my home base from zombie hordes. But I removed all of my outposts and fortifications. Then I systematically killed all of my characters that were good at fighting, while they were holding all of my most valuable weapons. I left two noobs in the base and they fought off eight waves of zombie hordes with a single frying pan between them. In other words, the point of the game is to defend your base, but if you don’t defend your base nothing happens.

So basically on my first play-through of State of Decay I was the six-year-old on the Autopia ride at Disneyland. I had a great time turning the steering wheel right and left, sure, but I thought I was driving a car when I was actually riding a train along a track. State of Decay is attached to a metal rail and the steering wheel is disconnected. I thought I was good at the game the first time I played it (blush), but now I know this is what I deserve:

This is a daring game design decision. In a sense all games are on that metal rail, but Undead Labs has really pushed it by creating an elaborate user interface for a nonexistent simulation game. I worry that some of it may have been inadvertent. That is, some of this stuff feels like the hooks for the simulation that Undead Labs intended to build but didn’t get around to. That would explain this Friday’s release of the first downloadable update to the game, a simulation mode (“sandbox”) called “Breakdown.” I guess most players (like me) thought that we already bought that the first time, but we did not.

I thought that State of Decay would be a game I might use to teach about simulation, but actually I think it is useful as a way to teach about honesty. I took the things in State of Decay that seemed random and imagined them to be spinning cogs of an awesomely complex simulation engine I could enjoyably reverse engineer at my leisure. But the engine in the original State of Decay seems random because is consists of a few wires connected to a random number generator.

That means my teaching questions would be these: In the original State of Decay I felt a big letdown when I worked out that there was nothing to work out. Is that an acceptable game design risk to take, as long as most players never find out they were tricked? At the same time, I was happy to be tricked when locked in BioShock’s little room. Later on, I found out that Bioshock tricked me, but that doesn’t bother me. What’s the difference?