The Ma were a family of Hui (i.e., Han Chinese Muslim) warlords in northwestern China in the first half of the 20th century, a bloody and complex period in the region. The two most famous members of the clan were Ma Bufang and Ma Zhongying, who fought with Chiang Kai-shek against the Communist forces. Ma Bufang ruled Qinghai from 1937 until the Communist victory in 1949. Ma Zhongying, was warlord of neighboring Gansu and fought unsuccesfully to control Xinjiang.

According to Wikipedia, Ma Zhongying fled to the Soviet Union and was probably executed by Stalin in a purge in 1937. After the Communist takeover, his cousin, Ma Bufang became the Taiwanese ambassador to Saudi Arabia although he was removed from his post in 1961 by the Taiwanese government after he forced his niece to become his concubine. He never returned to China and died in Saudi Arabia in 1975. There’s a book in here somewhere.

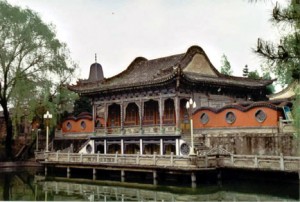

Ma Bufong’s palace in Linxia

[source]

hey ed, the name Ma Bufang (which I had heard from Tibetans as Ma Bufeng) rang a bell from a long biography of an older Tibetan nomad I was working on ages ago.

here, trusting that you really really are interested in Chinese Muslim warlords, is the text of her comments on Ma Bufeng. She lived in Khams – in eastern Tibet.

In the valley, there were two leaders. These leaders were Tibetans of course and they were both rich men, but they had made themselves rich by working, not by taking from other people. Everyone had to give taxes to our local leaders, who collected them all together and gave them to the head of the region of Tibet we were part of. Then this Tibetan leader passed them on to the Chinese far away in Seling, a big city that the Chinese call Xining.

Seling is where Ma Bufeng lived. Ma Bufeng was a Chinese Muslim warlord who we had to pay taxes to. We never saw Ma Bufeng but he and his soldiers loved to fight and kill. We paid them so they would stay in their country and not come to kill us. If a family couldn’t pay their tax, the Chinese would order the leader of that family to be beheaded. I never saw this happen but I heard many stories about it. It never happened in Bathang that I know of.

The amount of tax money we had to pay was very great. For example, our family had to give 15 sho of money. I cannot explain exactly how much that comes to in today’s money, but it was a tremendous amount, even for my family. The whole family—my brothers and all—used to have to work together very hard to raise those taxes each year. Then there were the taxes we had to pay not with money but in goods. There was a butter tax, a yogurt tax, even a tax of yak dung that we dry and burn as fuel.

It was complicated for the Chinese Muslims to collect all these things from each family and in Bathang, they forced us to put up a building so our local leader could count up all our taxes there. This was the only building in Bathang. Everything else was nomad tents. Later, when the Communists came, they used this building to hold meetings. But originally it was for counting Ma Bufeng’s taxes.

The Chinese Muslims also ordered us to buy guns to keep in our families. The reason the Chinese Muslims made this rule was because if they wanted to fight another country, they wanted to be able to order our local Tibetan leader to raise troops. When I was small, they never actually called our men out to fight, although a few times they had us prepare for a war. For some families this was very difficult because they had no extra wealth, nothing to trade for those guns.

This was completely different from how the Communist Chinese behaved later. After they arrived and got enough power, the Communists began to confiscate our guns. They would never ever have trusted us to fight on their side. The Chinese Muslims had some power over our local leader, but they didn’t try to actually rule us or force us to change our ways. They figured out how much they could take without our fighting them and that was all they asked for. Then they knew could trust us with guns. It wasn’t easy to give them so much of our wealth but on the whole it was much, much easier to live with the Chinese Muslims than with the Communists.

Mostly the Chinese Muslims who came to our area were businessmen and they only stayed in the summers in Kyigudo. When it began to get cold, they would leave. Only one Chinese man stayed in Kyigudo year-round back then.

In Bathang, the only time we ever even saw Chinese Muslims apart from tax-time was during our horse-riding competitions. We held these in the summers, in the seventh month of our calendar, for two days. All the most skillful horsemen from all around Bathang would compete to see who could do different tricks the best.

In the main contest, the horseman makes his animal gallop very fast and then he must touch his back to the ground while the horse is still running. He takes his whole body out of the saddle, with only one foot remaining in the stirrups. He just rides as long as he can like that, with his back touching the ground, then he gets back on the horse. There was another competition where the riders don’t touch their back on the ground, but they ride and shoot their guns at a target while they are moving.

Many, many nomads came from all around to watch this festival. Maybe fifty of the best riders in Bathang demonstrate their skills. My brother Tsawang became famous for the riding he did at these competition when he was very young—fourteen, fifteen, sixteen years old.

At the time of the competition, we made a big picnic every year. All the local families pitched a tent in the place where the riding would be. We cooked many different foods and ate them right there together while the festival was continuing. Normally we love to sing but we didn’t do any singing at this festival, only watching.

The Chinese Muslims also knew how to ride horses quite well and they used to like to come to Bathang to show what they could do. They had a trick of their own that they used to perform at this festival. They would begin to ride quite fast and then suddenly they would put their head down on the saddle, in the spot where your bottom belongs, and then stick their legs straight up in the air. They did this while the horse was still running. When the Chinese people did this trick, we thought it seemed very inauspicious, riding upside down with their heads in the saddle like that.

Other than that, we didn’t see those Chinese much. Still, we didn’t like to be under Chinese Muslims. Beside the taxes, their ideas and their ways were different to ours and we preferred to stay by ourselves and follow our own rules.